HMS Venerable

N50 25.760 W3 33.139

Select image below to view Project Report

Painting of Channel Fleet in Torbay

HMS Venerable team at Buckingham Palace. Team Leader Steve Clarkson

HMS Venerable was launched at Perry’s yard in Blackwall on 19th April 1784. It took approximately 4000 mature oak trees to build her over a two year period at a cost of approximately £3800. She was 170 ft long with a beam of 47 ft and weighed over 1650 tons. Many other ships were produced at the same yard including HMS Crocodile, a 24 gun sixth rate, who met her death not far away from HMS Venerable in 1784. Also not far away in South Devon, lies the wreck of another older ship, ‘HMS Ramillies’.

HMS Venerable was designed by Sir Thomas Slade, who was the ‘Surveyor to the Navy’ at the time. He had based his design on Spanish and French ships captured in the 1740’s.

Her first Captain is believed to be Sir John Orde, who joined the ship in 1794. It is unclear where the ship was in the 10 years after her launch in 1784 to 1794 and we are assuming, having been made of green oak, she was still in the water at Blackwall. We are still researching where she was over that period of time. One of the copper sheeting pieces recovered is dated 1794, which suggests she was not put into commission until that date. This may well be the date she was first sheathed.

A couple of her memorable events are summarised in the following section.

The Battle of Algeciras

There were two separate battles involved in this conflict.

The battle began on July 6, 1801, when the French Admiral Linois brought his three ships of the line and one frigate into Algeciras after finding that the British had blockaded Cádiz. No fewer than four Spanish forts protected the harbour at Algeciras, and so the French and Spanish considered it safe despite its proximity to Gibraltar.

The British observed these movements from Gibraltar, and decided to move quickly to try to neutralise this threat. On 8 July, a fleet under Admiral Sir James Saumarez sailed out from Gibraltar into the Bay of Gibraltar, intending to attack the French ships.

The British fleet consisted of six ships of the line. Saumarez had a seventh ship of the line, HMS Superb, but she and her accompanying brig, Pasley, were absent; Saumarez dispatched his sole frigate – the HMS Thames – to recall her, but they did not return in time.

The British squadron consisted of:

- Caesar 80 (flag of Rear-Adm. James Saumarez, with Captain Jahleel Brenton)

- Pompee 74 (Captain Charles Stirling)

- Spencer 74 (Captain Henry D’Esterre Darby)

- Venerable 74 (Captain Samuel Hood)

- Hannibal 74 (Captain Solomon Ferris)

- Audacious 74 (Captain Shuldham Peard)

The French squadron consisted of:

- Formidable 80 (flag of Rear-Adm. Linois, with Captain Laindet Lalonde)

- Indomptable 80 (Captain Moncousu †)

- Desaix 74 (Captain Jean-Anne Christy de la Pallière)

- Muiron 40 (Captain Martinencq)

Saumarez’s six ships attacked the French ships and Spanish forts, but a lack of wind and numerous shoals in the harbour hampered the attack. The French squadron, with aid from the forts and Spanish gunboats, held its own. They were able to drive off the larger British force, although the French purposely grounded their ships to avoid capture. Saumarez lost the 74-gun Hannibal after it ran aground near Spanish fortifications and was obliged to surrender,[1] which enabled the French to capture her. Calpe lost several men and boats attempted to rescue Hannibal’s crew. The rest of the British squadron suffered various degrees of damage and the British lost 121 men killed and 240 wounded. The French lost 306 killed, including Captains Laindet Lalonde and Moncousu, and 280 wounded.

Both sides retired to their respective sides of the bay, and over the next four days repaired their battle damage as best they could. The Pompée could not be repaired in the time available, and the Caesar was only repaired in time due to constant day-and-night work. The French refloated their ships and prepared them for sea.

The Battle of Camperdown

The Battle of Camperdown (known in Dutch as the Zeeslag bij Kamperduin) was a major naval action fought on 11 October 1797[Note A] between a Royal Navy fleet under Admiral Adam Duncan and a Dutch Navy fleet under Vice-Admiral Jan de Winter. The battle was the most significant action between British and Dutch forces during the French Revolutionary Wars and resulted in a complete victory for the British, who captured eleven Dutch ships without losing any of their own. In 1795 the Dutch Republic had been overrun by the army of the French Republic and had been reorganised into the Batavian Republic, a French client state. In early 1797, after the French Atlantic Fleet had suffered heavy losses in a disastrous winter campaign, the Dutch fleet was ordered to reinforce the French at Brest. The rendezvous never occurred; the continental allies failed to capitalise on the Spithead and Nore mutinies that paralysed the British Channel forces and North Sea fleets during the spring of 1797.

The Battle of Camperdown (known in Dutch as the Zeeslag bij Kamperduin) was a major naval action fought on 11 October 1797[Note A] between a Royal Navy fleet under Admiral Adam Duncan and a Dutch Navy fleet under Vice-Admiral Jan de Winter. The battle was the most significant action between British and Dutch forces during the French Revolutionary Wars and resulted in a complete victory for the British, who captured eleven Dutch ships without losing any of their own. In 1795 the Dutch Republic had been overrun by the army of the French Republic and had been reorganised into the Batavian Republic, a French client state. In early 1797, after the French Atlantic Fleet had suffered heavy losses in a disastrous winter campaign, the Dutch fleet was ordered to reinforce the French at Brest. The rendezvous never occurred; the continental allies failed to capitalise on the Spithead and Nore mutinies that paralysed the British Channel forces and North Sea fleets during the spring of 1797.

By September, the Dutch fleet under de Winter were blockaded within their harbour in the Texel by the British North Sea fleet under Duncan. At the start of October, Duncan was forced to return to Yarmouth for supplies and de Winter used the opportunity to conduct a brief raid into the North Sea. When the Dutch fleet returned to the Dutch coast on 11 October, Duncan was waiting, and intercepted de Winter off the coastal village of Camperduin. Attacking the Dutch line of battle in two loose groups, Duncan’s ships broke through at the rear and van and were subsequently engaged by Dutch frigates lined up on the other side. The battle split into two melees, one to south, or leeward, where the more numerous British overwhelmed the Dutch rear and one to the north, or windward, where a more evenly matched exchange centred on the battling flagships. As the Dutch fleet attempted to reach shallower waters in an effort to escape the British attack, the British leeward division joined the windward combat and eventually forced the surrender of the Dutch flagship Vrijheid and ten other ships.

The loss of their flagship prompted the surviving Dutch ships to disperse and retreat, Duncan recalling the British ships with their prizes for the journey back to Yarmouth. En route, the fleet was struck by a series of gales and two prizes were wrecked and another recaptured before the remainder reached Britain. Casualties in both fleets were heavy, as the Dutch followed the British practice of firing at the hulls of enemy ships rather than their masts and rigging, which caused higher losses among the British crews than were normally experienced against continental nations. The Dutch fleet was broken as a fighting force, losing ten ships and more than 1,100 men. When British forces confronted the Dutch Navy again two years later in the Vlieter Incident, the Dutch sailors refused to fight and their ships surrendered en masse.

HMS Venerable was launched at Perry’s yard in Blackwall on 19th April 1784. It took approximately 4000 mature oak trees to build her over a two year period at a cost of approximately £3800. She was 170 ft long with a beam of 47 ft and weighed over 1650 tons. Many other ships were produced at the same yard including HMS Crocodile, a 24 gun sixth rate, who met her death not far away from HMS Venerable in 1784. Also not far away in South Devon, lies the wreck of another older ship, ‘HMS Ramillies’.

HMS Venerable was designed by Sir Thomas Slade, who was the ‘Surveyor to the Navy’ at the time. He had based his design on Spanish and French ships captured in the 1740’s.

Her first Captain is believed to be Sir John Orde, who joined the ship in 1794. It is unclear where the ship was in the 10 years after her launch in 1784 to 1794 and we are assuming, having been made of green oak, she was still in the water at Blackwall. We are still researching where she was over that period of time. One of the copper sheeting pieces recovered is dated 1794, which suggests she was not put into commission until that date. This may well be the date she was first sheathed.

A couple of her memorable events are summarised in the following section.

The Battle of Algeciras

There were two separate battles involved in this conflict.

The battle began on July 6, 1801, when the French Admiral Linois brought his three ships of the line and one frigate into Algeciras after finding that the British had blockaded Cádiz. No fewer than four Spanish forts protected the harbour at Algeciras, and so the French and Spanish considered it safe despite its proximity to Gibraltar.

The British observed these movements from Gibraltar, and decided to move quickly to try to neutralise this threat. On 8 July, a fleet under Admiral Sir James Saumarez sailed out from Gibraltar into the Bay of Gibraltar, intending to attack the French ships.

The British fleet consisted of six ships of the line. Saumarez had a seventh ship of the line, HMS Superb, but she and her accompanying brig, Pasley, were absent; Saumarez dispatched his sole frigate – the HMS Thames – to recall her, but they did not return in time.

The British squadron consisted of:

- Caesar 80 (flag of Rear-Adm. James Saumarez, with Captain Jahleel Brenton)

- Pompee 74 (Captain Charles Stirling)

- Spencer 74 (Captain Henry D’Esterre Darby)

- Venerable 74 (Captain Samuel Hood)

- Hannibal 74 (Captain Solomon Ferris)

- Audacious 74 (Captain Shuldham Peard)

The French squadron consisted of:

- Formidable 80 (flag of Rear-Adm. Linois, with Captain Laindet Lalonde)

- Indomptable 80 (Captain Moncousu †)

- Desaix 74 (Captain Jean-Anne Christy de la Pallière)

- Muiron 40 (Captain Martinencq)

Saumarez’s six ships attacked the French ships and Spanish forts, but a lack of wind and numerous shoals in the harbour hampered the attack. The French squadron, with aid from the forts and Spanish gunboats, held its own. They were able to drive off the larger British force, although the French purposely grounded their ships to avoid capture. Saumarez lost the 74-gun Hannibal after it ran aground near Spanish fortifications and was obliged to surrender,[1] which enabled the French to capture her. Calpe lost several men and boats attempted to rescue Hannibal’s crew. The rest of the British squadron suffered various degrees of damage and the British lost 121 men killed and 240 wounded. The French lost 306 killed, including Captains Laindet Lalonde and Moncousu, and 280 wounded.

Both sides retired to their respective sides of the bay, and over the next four days repaired their battle damage as best they could. The Pompée could not be repaired in the time available, and the Caesar was only repaired in time due to constant day-and-night work. The French refloated their ships and prepared them for sea.

There is a statue of Jack Crawford in Sunderland dedicated to his contribution in the battle. When the colours were shot from the mast ( a sign of surrender) Jack recovered the colours and climbed the mast to put them back. This is where ‘Nailed the colours to the mast’ originated. This ultimately led to the victory.

There is a statue of Jack Crawford in Sunderland dedicated to his contribution in the battle. When the colours were shot from the mast ( a sign of surrender) Jack recovered the colours and climbed the mast to put them back. This is where ‘Nailed the colours to the mast’ originated. This ultimately led to the victory.

The successful split formation used in the battle was one that was adopted by Nelson at Trafalgar years later. Nelson always has a painting of Duncan in his cabin. He did later acknowledge the fact it was Duncan’s idea.

Sunderland Maritime Museum

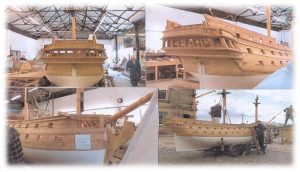

It was extremely interesting when Neville Oldham and Dave Parham found a group of ordinary people who worked in the shipyards on the banks of the River Tyne who, when the yards closed down, decided to create a working museum dedicated to the ship building industry that had disappeared, where they could pass on their shipbuilding skills to future generations, giving their time free and financing their enterprise by repairing old vintage wooden boats.

They formed Sunderland Maritime Heritage. One of their first aims was to try to save the City of Adelaide, a 19th century schooner, the hull of which is still intact and lying in Glasgow. They wanted to get her back to Sunderland where she was originally built so they could restore her.

Amazingly, the crafts-men of SMH in six weeks built a large scale replica of her to take round to local events to raise money for the project.

Inspired by this, they decided to build a quarter scale model of HMS Venerable. This was not just as a salute to their local hero but to train young shipwrights in the construction of wooden ships.

Inspired by this, they decided to build a quarter scale model of HMS Venerable. This was not just as a salute to their local hero but to train young shipwrights in the construction of wooden ships.

The following pictures give you some idea of the model and its scale.

A small number of artefacts from HMS Venerable have been loaned to the museum by Neville Oldham and it is hoped we can loan them more on completion of this project.

See their website at : www.sunderlandmaritimeheritage.org.uk

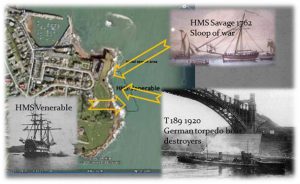

Other Wrecks in the area

The following diagram shows some of the position of some of the wrecks in relation to the identified site.

After the First World War, many captured ships were towed to scrap yards in the UK. T189 was one of these ships and was due to be scrapped and was on tow to Teignmouth from Cherbourg in France. The T189 was a German torpedo boat destroyer.

On December 12th 1920, she was under tow with a similar boat, by a the London Tug ‘warrior’, when both torpedo boats broke loose from the towlines. The strong wind from the East had turned into a gale. She was driven into the rocks off Roundham Head at about 11pm that night. The S24 that had also broken loose ended up on Preston beach the same night. All the crew survived and those on the T189 were taken ashore with a rocket apparatus.

The wreck has been extensively salvaged over the years, mostly by ‘Dynamite Jim’ from Paignton.

Some sections of the wreck are under the sand laying over the HMS Venerable site, making it difficult to stop the underwater metal detectors triggering. Some sections are large enough to swim through as shown below.

Her Final moments

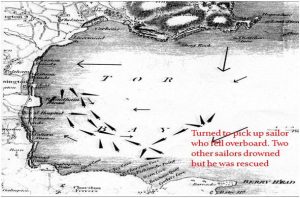

HMS Venerable is the only British man-of-war known to have been lost because a man fell overboard! On Saturday 24th November 1804, the Channel Fleet was at anchor in Tor Bay. One ship was the third-rate 74-gun HMS Venerable, under the command of Captain John Hunter. At 3pm, the wind suddenly shifted wildly from west to north-east. With the wind came rain, blotting out most shore marks. At 4.30pm as the wind increased, the admiral decided his ships would be safer out at sea and made the order to sail. The Navy crews raised their anchors and were lashing them to the catheads as they fought their way out of Tor Bay against the wind. In Venerable, all was going well, but just as the men were “in the act of hooking the cat”, a seaman fell overboard from his perch on the anchor itself.

The cry of “man overboard” sent crews rushing to launch a boat. In the dark and rush, one of the ropes was let go too soon, the boat tipped and Midshipman J. Deas and two seamen were thrown out and drowned. The boat lowered on the other side of the ship managed to pick up the man who had fallen overboard from the anchor. While this rescue was being carried out, the foresails and topgallants were set, but all the time the ship had been falling back and was now unable to weather Berry Head. They tacked and headed north but found themselves nearly running down other ships of the fleet.

In avoiding collisions, they lost more ground and suddenly on tacking, found themselves near the lights of Paignton. They tried once more to round Berry Head, but could not make it and north they went again. Another ship loomed ahead of them and in avoiding her they lost more ground. At 8.30pm the wind died and as it did so the big warship touched bottom and then grounded hard. The rain stopped and they could see that they were “under Paignton cliffs”. The Venerable was held by rocks fore and aft.

The lull did not last. The wind came back full from the east and the sea came up with it. The crew tried to cut the masts away so that they would fall between the ship and the shore, but failed. Distress signals were fired as the ship seemed likely to capsize. By 10pm the water was up to the lower gun deck inside and huge waves were breaking right over the ship. HMS Impetueux was anchored close by and lowered herself back on her cable until she was within 600 yards. HMS Goliath did the same and both sent their boats out to the stricken ship. The men on the Venerable dropped into them from the stern ladders in a wild rescue relay amongst the enormous surf.

At midnight, the Venerable was almost right over and soon after the last man was taken off she broke in two amidships. Shortly after that Captain Hunter saw his ship “break into a hundred thousand pieces” but the loss of men, thanks to Impetueux and Goliath, which took off 547, was only eight, including the midshipman and two sailors who drowned trying to rescue the man overboard.

Captain Hunter told his court-martial – at which he was acquitted – that his crew were so brave that he would be glad to have all the men but one with him in any other ship. The one he rejected was a private of the Marines, David Evans, who, during that dreadful night, was dragged on deck drunk still clutching “a tin kettle of port wine”. His pockets were stuffed with articles of officer’s apparel that he had stolen from the wardroom. It is doubtful if Evans was able to serve in any other ship anyway – he was given 200 lashes of the cat-o’-nine-tails on his bare back during a beating round the Fleet some weeks later.

Most of the guns of the Venerable were salvaged. However, divers on the site have found cannonballs and quite a lot of small lead shot. The wreckage is 350 yards to the south-east of the southern end of the beach.

The following chart shows the track of HMS Venerable from when her anchor was raised to her eventual demise on Roundham head. Stephen developed this from the court marshal information.

Salvage

In 1835 the Deane brothers demonstrated their diving skills in Torbay harbour and moved on to salvage the Venerable. Being so close to the shore the local started salvaging her the day after she sank and there is even a report of the landowner being shot in the shoulder by the military whilst he was involved in this salvage. The Deane brothers removed the cannons as well as small artefacts and sections of worm holed timber, currently in Portsmouth Museum. During the 70’s and 80’s, local divers recovered most of the small artefacts visible. One of the divers, Stephen George, has participated in this project and gave me most of the items listed in the following section.

The HMS Venerable Project won the BSAC Duke of Edinburgh “Highly Recommended” Prize and went to the Palace to collect the award. See Below

From left to right

Neville Oldham, Rod Howell, Jessica Berry, Steve Clarkson, Mike Turner, Nick McVernon, Duke of Edinburgh, John Bawden, Alison Bawden, Clive Weatherby, Katalin Weatherby and Dave Parham